ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT OF THE CITY OF SPLIT IN THE INTERWAR PERIOD IN THE LIGHT OF NATIONAL AND SOCIAL TURMOIL'S

Introductory remarks

The city of Split is the largest city in Dalmatia and the second largest

in Croatia, after the capital Zagreb. According to the last census (2011), the

Split counts 178 102 inhabitants,[1]

and it is a leading regional urban center

for the southern Croatian coast. Its Metropolitan region includes a wide area

of the coastal territory: from the town of Trogir to Omiš, covering a large

part of the Dalmatian hinterland and the nearby archipelago. As a city oriented

towards the sea, it is the second largest maritime port in Croatia, after the

city of Rijeka. Also, it is the administrative center of Split-Dalmatia County.

Split is

situated on an elongated peninsula under the hill of Marjan and is separated

from the hinterland by karst massifs of Mosor and Kozjak. Such location and

pleasant Mediterranean climate conditions caused the early presence of

residents in this area. The origin of the town is typically linked to the

building of the palace of the Roman emperor Diocletian in the late third and

early fourth century, though most likely in the pre-Roman period an

Illyrian-Greek settlement had existed at the south side of the Split’s

peninsula. After the fall of the Roman Empire and the arrival of the Slavic tribes

in this region in the seventh century, the former imperial palace became the nucleus of a future life, serving as a

settlement for newcomers. Already in the Middle Ages, Split was an autonomous

community, and from 1420 to 1797 was annexed to the Venetian Republic. During

the nineteenth century it was under the French and later the Austrian rule

until the end of the World War I. After two periods of Yugoslavian governance,

in 1991 the city became a part of the independent Republic of Croatia.

The

history of the city is marked by many urban, demographic, economic and

administrative fluctuations. Its urban organism existed and thrived both in

prosperous times as well as in historic stages of regression, disease, hunger

or wars that resulted from different political aspirations. Special place in its

long history occupies a period between the two world wars that is, regardless

of the World War I sufferings and political turmoil’s, marked by a strong

demographic and urban growth. The story of Split’s

architecture during the first half of the twentieth century is an instructive

and interesting example of how smaller provinces – compared to the centers of

political and financial power – with their vitality and help of talented and

enterprising individuals, managed to arouse, developing their own strengths with the objective of

economic and urban progress. From this standpoint, the paper analyzes the urban

activity in the city during the interwar period.

Introduction:

the city of Split at the turn of the twentieth century

Split’s

community entered in the twentieth century with an increased local awareness on

identity, but also with the burden of the progress that has brought

technological and civilizational development. From the inner city, located

within gorgeous Early Modern bastions, which were built to defend against the

Ottomans, the city urbanized area begun to spread in the surrounding fields and

an attempt to regulate its south sea front were conducted at the same time.[2] Thus, in

the prewar period, the city had expanded its boundaries in all geographical

directions; this indicates the spatial expansion that will intensify after the World

War I years. The development of civil society in the town during the nineteenth

century, including its social and cultural dimension, also continued during the

first decade of the twentieth century.[3] This continuity

is reflected in community, church and family traditions, romantic notions of

nationalism and lively participation of writers and artists in the everyday public

life of the city. The prewar time is also a period of such life and everyday

circumstances, that had begun to wane before the new "democratic, Slavic

and cosmopolitan ideas and influences."[4]

In political and administrative

terms Split was, just like the rest of the Croatian territory, a part of the

Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and acted as a center of its Dalmatian province. At

the end of the imperial period, demographic growth was very remarkable: before

the war the city counted about 24 000 inhabitants.[5] By that

time Split has already had the basic transport and infrastructure network

established,[6]

becoming an important transportation hub and a developing seaport for export

(especially wine and cement); industry has recently developed in the wider

metropolitan area. The spatial structure of the city in the prewar period

consisted of an ancient and medieval town surrounded by the Early Modern fortification

system, and some rural suburbs of Veli Varoš, Dobri, Manuš and Lučac around it.

Bastion fortifications at this time no longer served their purpose and were

breached in several places in order to enable transport and functional

communication between older and newer parts of the developing city. At certain

places the former defensive zone was reconstructed, including location of the new

public buildings: in 1893 the Municipal theatre was finished; in 1903 the Sulfur

spa baths building was completed; in 1904 the monumental Bishop’s palace was

finished; in 1908 the representative eddiffice for the “National home” opened

its gates; in 1909 construction of the east wing of the large municipal

building called Prokurative was initiated and in 1910 a large high school

building was constructed.[7]

Regarding Split’s tendency of

permanent spatial expansion, preparation for the urban plan soon begun. The

idea and aim of this initiative was to prepare an outline for a long-term urban

construction within the city boundaries. Thus, in 1905 the municipal

administration received permission (by Dalmatian parliament as a representative

political body of the Dalmatia, under Austrian rule) to produce footage of

metropolitan area that was to serve as a basis for a future construction

activity.[8] After

the technical elaboration, the project was finished in 1914 and was published as

the first urban map of the municipality.[9] Its main

characteristic related to predictions of future urban interventions in the wider

area surrounding the city. Urban development plan was prepared by the local engineer

and architect Petar Senjanović (1876-1955) and represented the first attempt to

regulate the development of the city. Although the plan had an elements of

schematic nature with no real urbanity elaboration (it was not constitute as an

official zoning guideline), but its importance should be seen in the long-term

urban planning ideas for the new, unbuilt zones of the Split’s peninsula,

taking into account the perspective of industrial development and permanent

population growth.[10] The plan

provided the development of residential areas in the wider area of the city

port and in the north part of the city boundaries, while the industrial zone was

proposed in the northern coastal line of the peninsula and along the

Kaštelanski Bay.[11]

With maximum capacity use of the harbor, the plan envisaged the construction of

a new industrial port north of the city (zone Poljud), that would have been connected

by the railway with the hinterland.[12]

Shortly before the war, urban

expansion was manifested by construction of many family villas.[13] They

grow out from old fields and vineyards while today are incorporated in modern

urban tissue that is fully covered by the mantle of ferroconcrete

constructions.

Regardless of the perspective plans

of growth of the city in the economic, demographic and urban sense, World War I

stopped any construction activity.[14]

The

First World War and its consequences for Split

The

negative impact of the Great War was evident in all areas, economic, social and

cultural. The war and the first postwar years brought a decline of every form

of urban life in Split that was affected by a great shortage of food. Split’s

chronicler from the 1930s Branislav Radica noted:

The city rusty, muddy and dusty

with the broken streets, scarce sewage and water, without light, gas and coal.

Complete suspension of any economic life. The shortage of food. High cost of

living, idleness, misery and poverty. Great masses of soldiers of smashed

Austrian army, refugees from the occupied territories, officials from the occupied

Zadar, starving peasants from the hinterland. Bolshevized crowd. Foreign fleets

and mission, admirals and generals, attaches and inspectors, who determinate

the rights and power for themselves. Italian occupation of the surroundings.

Harbors deserted. Communications by the sea and land a scarcity, irregular and

interrupted by frequent blockages. Municipal coffers empty, funds invested in

war loans, institutions and businesses ruined, with no money and materials.

Large housing and offices shortage. Administration irregular and powerless. The

continuing danger from the undisciplined, idle, hungry masses that can cause

trouble, which in those conditions could result with endless consequences.[15]

This is a picture of Split after

the end of World War I. “The horrors of war opened up abysses of fear, anxiety,

and loneliness.”,[16] as one

scholar noted. Bringing people to the edge of endurance, the war impoverished

the whole Dalmatia.[17] What is

more, for a long time after the war, the population of Split was psychologically

affected by the memories of terrible war scenes and its tragic consequences.[18]

Croatia had entered the war as part

of a very complex and conflict-laden state, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. More

than a hundred years of Austrian government in Dalmatia was not a time of

special prosperity or strong economic growth of the region.[19] During

the National Revival in the latter half of nineteenth century, the Italian political

influences and the autonomist, pro-Italian orientation in Dalmatia was overpowered

by the populist, pro-Croatian movement that saw prosperous future of Dalmatia

in its connection and finally union with continental Croatian lands. In the

postwar period several new nation-states were established in this region and the

State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (which in 1929 became the Kingdom of

Yugoslavia) was one of these new political entities. However, pro-Serb policies

that dominated internal policies of this country caused the occasional public

revolts.[20]

After the war Split became a part of this unstable political entity.[21]

Different, often contradictory political formations, ideological subdivision of

the public sphere as well as the effects of wartime, certainly did not

guarantee civil peace and economic prosperity. Hence, such conditions did not

provide any fertile ground for artistic creativity and expression.

However, the social and political

situation within the city was relatively quickly stabilized after war. Despite

difficult conditions of Split mentioned above, the construction market very

fast regained its strength. As I mentioned, the Split’s architecture during the

first half of the twentieth century is an instructive and interesting example

of how smaller provinces – compared to the centers of political and financial

power (especially in Serbia) – experienced vitality and help of talented and

enterprising individuals and managed to arouse and develop their own economic

and urban progress.

In

the decades between the First and Second World War life in Dalmatia retained

the essential features of its Mediterranean surroundings in all forms.[22] As

stated, until the end of nineteenth century urban life of Split was most of all

concentrated in the city antique and medieval core. It was on all sides

embraced by rural suburbs-boroughs which gradually became new centers of civic

life, subsequently spreading further into Split’s adjacent fields.[23] Later,

this spatial expansion was connected with a new standard of living outside of the

colossal walls of the old city core that was favored by a range of

architectural interventions that completely changed the urbanscape of the historic

city.

Political, social and economic situation of Split in

the interwar period

During the war, the politics of Italian irredentism was a major

problem for the Croats in the basin of Adriatic Sea. Italian prewar plans for

the occupation of the Adriatic coast were soon materialized, so Dalmatia was conquered

in November 1918. First of all, Italian forces have been occupied islands of

Vis, Lastovo and city of Šibenik, and later other places on the Dalmatian

coast.[24] Under the pretext of peacekeeping Italians numerous military troops

arrived. Soon after, admiral Enrico Millo declared himself as Italian governor

of Dalmatia.[25] Two years later, Split and most of Dalmatia were annexed to Kingdom

of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

It was

also a period of sharp national and class struggle for political and social

rights of the people led by the Communist Party. Later, it turned out that

these turmoil’s had prepared ground for the revolution that happened during the

National liberation war.[26] Under the influence of the Croatian Peasant Party, the pro-Yugoslav

and the pro-Serbian tendencies were gradually replaced by the Croatian one.[27] Nevertheless, some radical Yugoslavia-oriented political attitudes

still remained influential and dictated life and culture in the city.[28] After the war and the initial idea of communion of South Slavic

nations, centralist and absolutist ideology that was developed in Serbia,

increasingly dominated the public life. Among other things, this domination was

manifested by many death sentences, political murders and arrests of political

opponents.[29] Soon, this accelerated the process of rejection of idea of integrated

Yugoslavianism. As a consequence, the Croatian Peasant Party was consolidated

as the strongest party group in Dalmatia, so Croatian national integration

processes leaded to the formation of the strong Croatian identity with the vast

majority of the Catholic population.[30] However, in the new state the city had many economic, social and

even political conditions for development, though civil liberties were

restricted, until the establishment of Croatian Banovina in 1939, when

suppressed Croatian spirit became a little more prominent.[31]

After

the war, as a consequence of the Rapallo and Rome Treaties of 1920 and 1924,

Trieste, Zadar and Rijeka were annexed to Italy. Hence, Split became the new

administrative, economic and cultural centre of Dalmatia,[32] and

also the main seaport of the new Kingdom.[33] The economic

arousal of Split in the interwar period was based on the development of the

cement industry, transport, shipbuilding, trade and commerce.[34] Also,

food industry, non-alcoholic and alcoholic beverages and mining, played

important role in the local economy. At the same time, modern services

developed, providing institutions of health care, education, culture, art

activity and sports for the community.[35] Unlike

the present, tourism and catering were poorly developed. The interwar Split was

mainly a transit town acting as a seaport and a railway hub. Foreigners have

begun visiting the area of Split and Dalmatia only since 1922, when diplomatic

relations with Italy were stabilized and when the greater part of the Italian

occupation forces were withdrew. In the interwar period, Split possessed 9

hotels, 32 hostels, and 19 restaurants.[36] In 1923

the "Society for the transport of passengers" was founded in order to

improve tourism services in the town; later many more associations and

companies were established in order to increase the quality of services,

promoting hospitality and tourism.[37]

Political

decisions impacted further development of the town substantially.[38] The

local economy was on arousal, the population grew and Split’s urbanized area

very soon was expanded, incorporating the rural areas around the city. After

the establishment of the new state, the new municipal council in Split was

organized and very quickly its members worked to improve decrepit communal

services and to solve town’s problems of transport connections with the

hinterland.[39]

The list of the main investments that will be discussed below includes creation

of the new urban regulation plan, construction of new rail connections with the

interior of the state, construction of the new north port and development of

waterworks.

The interwar modernization and expansion of Split

“At

the turn of the 19th into the 20th century, new buildings

mainly ranged from neo-styles spread throughout Europe. Until the World War I,

it was being built in the neo-styles in Split and these were the most prominent

public buildings, whose completed projects came mostly from the technical

department of the Ministry in Vienna.”[40] Also the

first postwar decade was a time of original and complex initiatives attractive

for the constructors and was crucial to the new role of Split as a major

seaport.[41]

In that time Split possessed a number of educated architects who had completed

their studies across Central European capitals (especially in Vienna) and who

started to design Split’s new urban structures, basing on their knowledge and

architectural vocabulary. Among others, it is important to mention Kamilo

Tončić (1878-1961), Fabijan Kaliterna (1886-1952), Žagar brothers (Eduard 1875-1957,

Danilo 1886-1978), Harold Bilinić (1894-1984) and Ivan Meštrović (1883-1962).

All of them more or less adapted the Art Nouveau artistic atmosphere and ideas that

was manifested through individual approach and treatment of architectural tasks

in their realizations. Also, some architects preferred eclecticism and neostyle

architectural modes.

Regarding

other artistic disciplines, the cultural scene of Split also became blossom

during these decades. For example, personalities such as Ivan Meštrović, Toma

Rosandić (1878-1959), Branislav Dešković (1883-1939), Emanuel Vidović (1870-1953)

and a range of other painters and sculptors worked in the newly established art

associations such as “Literary-artistic

club” or “Medulić society”.[42]

Interwar Split, as a culturally potent and creative environment influenced this

cultural renaissance. Despite political, economic or social turmoil’s, Split’s

artistic community have continued its rich artistic tradition and trajectory of

artistic development and creation, especially fruitful during the interwar

period. Demographic, architectural and urban development discussed above played

an important role in stimulating this artistic bloom, and the spatial expansion

of the city transformed Split into a functionally and topographically modern

urban environment.

In

spatial terms the historical, medieval centre with Diocletian’s Palace was an

area that was discussed through certain urban ideas developed in intention to

improve the living conditions in its narrow streets and presenting its cultural

monuments in a new way. Widening of the two main antique streets (Cardo and Decumanus) that pass through the Palace in order to achieve wider

pedestrian zones and better views of antique monuments was planned. Such far-reaching

reconstruction ideas were not totally acceptable so this idea was only partially

accomplished. Also terrains fit for new construction were secured along the

coastline in the direction of Bačvice Bay in the east, as well as in the west,

in the city area of Meje.[43] Another

zone was formed in the new area of Spinut, where new buildings were constructed

in a healthy environment, fully equipped with communal services.[44] The

space of the city harbor was also likewise changed: gradually, industrial

facilities were moved out of its western part. Its central part, the Riva, was

rearranged and the main promenade became the favorite meeting place for

citizens. A new industrial and trade area was formed at the northern side of

the peninsula, in the area of Kaštelanski Bay, comprising a cargo port, a

railway station, a wharf, and other facilities.

Regarding

electrification, water supply and sewage, Split was backward when compared with

other cities (Zagreb, Osijek, Zadar, Šibenik). The basis of the water supply

system in the town was the Roman aqueduct, which was modernized in 1922 to fit

for the enlarged city districts that were created at the edge of town. In 1932,

the city administration raised the loan from the “State Mortgage Bank” to expand

and modernize a water supply system. The town was electrified in 1920.[45] Construction

of the new, modern roads also begun at the time that was a period of expanding,

extending and building of new asphalt streets and railroad tracks.[46] Already

at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth-centuries Split’s harbor traffic

has rapidly increased, surpassing Zadar and becoming the leading Dalmatian port.

In the interwar period Split possessed two harbors, the one at the south and

another one in Solin-Vranjic area on the north side of the city.

Communal

investments also included new schools and public buildings, and a new public

garden that was established at Marjan hill, while city area of Lovrinac was

designed as a new cemetery. Southern promenade (Riva), where the Diocletian's

Palace formed the main historical building, was planted by palm trees. List of

improvements included also new football field and new Bačvice beach.[47] Also,

historic preservation of the Split’s heritage should be underlined: the most

important intervention was regulation of the southern front of Diocletian's

Palace,[48] designed

by Austrian architect Alfred Keller (1875-1945), winner of the international

competition (1923-1927).[49] In the

period of twenty years between the two world wars several crucial municipal

investments were conducted that included infrastructure, roads, streets,

electric and gas installations and water supply, sewage and green areas. All of

these were very necessary because of the dynamic of town’s development.

Searching for metropolitan identity: the interwar

urban plan of Split

The

preparation of the urban development plan (including a general and preliminary

plan with detailed layout and sections) was continued immediately after the

war. Concerning the spatial development of the Split’s peninsula at the time it

is evident that it basically followed the urban planning tendencies that had

been founded by the prewar plan discussed above. But, the new postwar projects

were based on international competitions. The most notable one was competition

for the municipal urban plan of regulation. It was announced in 1923, and 19 entries

were send by domestic and international planners and architects. The jury

commission was composed by the Mayor Dr. Ivo Tartaglia (1880-1949) and some

well-known European experts such as architects Herman Jansen (1869-1945) and

Leon Jaussely (1875-1932).[50] The

equal prizes were given to German architect Werner Schürmann who worked in the

Hague, and a group of architects from Vienna: Erwin Böck (1894-1966), Alfred

Schmid (1894-1969), Fritz Zotter (1894-1961) and Max Theurer (1878-1949).[51]

In

1925 Schürmann came to Split at the invitation of the Municipality. During

eight months of stay he created detailed urban planning sketches for certain

parts of the city.[52] His idea

envisaged the expansion of the town around existing parts along the harbor in a

semicircle, mainly to the east and north. With some other deficiencies, the plan

would not have changed existing main roads, residential streets and walkways,

and meandering streets that he proposed were the result of the author's efforts

to create a distinctive "Mediterranean atmosphere".[53] This

cultural approach was manifested by such a network of street that reflected in

a larger scale traditional street layouts of smaller Dalmatian towns. They were

more or less randomly built over past centuries so their urban landscape was

not the result of a rational, strictly planned construction. Hence, Schürman’s plan

had not a regular geometric (orthogonal or radial-concentric) scheme of street

grid. In 1928 the plan was approved by the Grand Prefect of the Split’s area.[54] Afterwards,

the reality modified Schürman’s ideas towards regulation, because of the

growing development of industry, rising of port traffic and the expansion of

residential areas outside of the boundaries of the accepted plan.

In

the final proposal of the plan, special attention was focused to the major

transport routes and the new railway station. The new port was planned in the

northwest part of the city. According to the plan, the old city core was no

longer able to remain the center of the city without major reconstructions and

modifications of architectural heritage.[55]

Therefore, the new civic and commercial was proposed on the northern periphery,

next to the main traffic lines. It would have been consisted of a new complex

of public buildings, such as cathedral, theater and large public square. Hence,

historical center would have been transformed only to extent required by modern

hygienic and traffic reasons. Schürmann saw optimal solution for the old city

core in optimizing the number of inhabitants, reducing density and restoring

historical buildings for public use. He also proposed demolition of some

significant antique monuments and suggested a number of expansions of

pedestrian streets.[56] Considering

that Split lacked public parks, he also planned to afforest several areas

within the municipal boundaries.[57]

Schürman’s

plan was never implemented due to the constant changes, additions and

modifications. The city proposed by Schürman was designed for 110 000

inhabitants, and Split at that time counted only 40 000.[58] In

1939, further amendments of the plan were almost completed so that the

procedure of completing the plan was finished in 1940. After its adoption, this

ambitious project was not materialized because of the beginning of the World

War II. Fascist occupation (1941-1944) stopped any urban activity in the city.

Split was also stroked with air bombardment by the Italians, the Germans and

the Allies.[59]

After terrible war ravages, the new initiative of the preparation of the new

plan begun in the 1948.[60]

Conclusion

It has been

long ago agreed that the “city” is organism, a living area, a microcosm that

coated shores, estuaries, valleys and plateaus. It is also a stage of human

efforts, aspirations and possibilities, vast and eternal exhibition of

architectural staging. Grows out of the core, developing its bloodstream

through the time and space, it modifies itself and blossom into a serious

figure subject always redoned to the current human world-view, opportunities

and urban thinking. Like its creator, sometimes it backs away, out of power,

slumps in its despair, but still pulses, vibrates like a deep seismic waves,

and waiting for its moment to bloom. It newly matures, spreads and grows,

chewing rural landscape and finally exists within its nodal and metropolitan

regions. On its life journey it constantly transforms and clothe the historical

times robes that are often discarded and resorted with new ones, while

inheriting in front of the eyes of the world the most beautiful and the most

valuable ones.

The

fluctuating urban ‘sensibility’ characterizes the second largest city in

Croatia – Split. From the times of Diocletian’s Palace to the modern era it has

undergone several significant changes and misfortunes, but a special place in

its rich history surely occupies the period between the two world wars. After

one hundred years of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy rule in this territory, the

city was in a whirl of World War I, from which emerged weakened, wrecked and

impoverished, in the new political arrangement known as the State of Serbs,

Croats and Slovenes. Although the wounds of war have left deep mark on the

urban and demographic structure, Split soon experienced very rapid civilization

prosperity thanks to the excellent geo-strategic position on the coast and

strong will by its inhabitants to revitalize their environment. But the

consequences of the war are not the only fact that barred the way for progress,

but also the complex political situation in the new state formation, which is

manifested through the absolutist and centralist government, pro-Serbian

political administration.

Nevertheless,

as the largest sociological value of the interwar years, the collective

dignity, civilization and civil way of life of its population coming to the

fore. A result is a range of architectural and urban planning, infrastructure,

horticultural and other projects that were starting to be implemented in the

metropolitan area. The city has expanded its boundaries by spreading from a

small town on the coast to an international seaport, at the same time

attracting people from the hinterland and developing the economic sector based

on industry, shipbuilding, transport and trade. Precisely, this is the

beginning of the modern Split.

|

Satellite image of the modern Split (personal archive: Damartem)

|

|

View of the modern Split from the west (personal archive: Damartem)

|

|

View of the city port from the east (personal archive: Damartem)

|

|

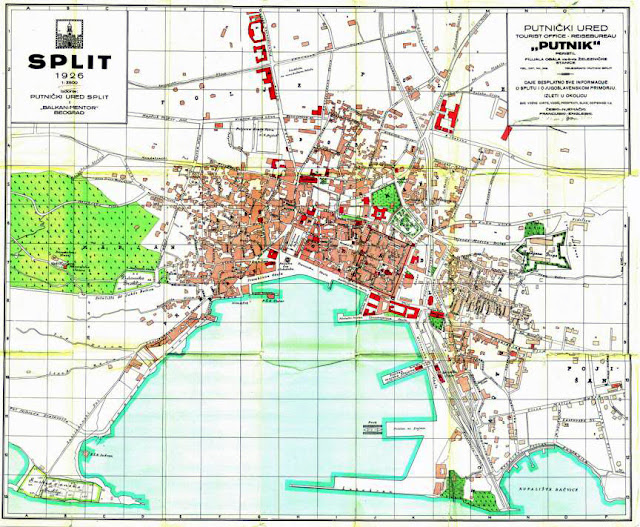

Urban situation in Split on the map from 1926

|

|

Drawing of the Split from 1926

|

|

Split city port in mid-1920

|

|

Split city port in the pre-war period

|

|

View of the city port from 1930s

|

|

View of the city center from the southeast

|

|

Aerial photo of Split

|

|

Urban development plan

from 1914 by Petar Senjanović, detail

|

|

Municipal urban plan of regulation from 1924 by Werner

Schürmann (personal archive: Damartem)

|

APPENDIX

Below are listed major

architectural, urban planning, infrastructure and utilities works in Split from

1919 to 1941.

The chronological list of

building and urban planning activities of the city of Split in the interwar

period:

- In 1919 a new public beach Bačvice was

opened on the southern coast of the Split’s peninsula.[61]

- In 1919–1920 the steps in the town

forest-park Marjan were built, connecting the west coast port and the plateau

in front of the Jewish cemetery. The staircase is made of white stone, with a

fence of vertical columns of the same material. The designer of staircase and

other actions on the Marjan hill was the architect Petar Senjanović, in

cooperation with the architect Prosper Čulić. In 1924 was carried out a staircase

to the second peak of Marjan.[62]

- In 1920 the city received electric

lighting.[63]

- In the early 1920s the main city coast

(Riva) was regulated in front of the southern front of Diocletian's Palace. In

1923 the demolition of old buildings in this area begun, which were in the seventeenth

and eighteenth centuries built below of cryptoportici of the Palace.[64] Until 1927 they were gradually replaced by new

‘minimum design’ houses designed by Viennese architect Alfred Keller, [65] winner

of an international competition.

- In 1921 the avenue of mulberry trees on the

waterfront was replaced by palm trees,[66] which were taken from the nursery from the island

of Vis.[67] Two rows of palm trees along the coast were installed in 1922 and 1927,

and palm trees in front of the Diocletian’s Palace in 1926. In 1911 double row

of mulberry trees were removed from Prokurative (a large square in the western

part of the city), than were in 1924 planted palm trees, which have been

removed again in 1937 from this square in order to exploiting it for festival

events.[68] At the Bačvice beach it was built a three-storey

building of Dvornik family, in which was opened the hotel "Imperial".[69] The designers were architects Fabijan Kaliterna and

Vjekoslav Ivanišević. Today it is a modern building of the hotel

"Park", which was in 1938 increased by the addition of side wings and

upgrades by one more floor. The World War II destroyed entire interior of the

building, and from 1948 to 1950 it was restored by the architect Dinko

Vesanović.

- In 1923 an international competition for

the regulation plan of Split was announced. Based on the ideas of Dutch

architect Werner Schürmann, [70]

later it was made a definite regulation plan of the city, which was in force

until 1941. The concept of this plan is a mediterranean town with winding

streets and public indoor areas, without much differentiation of traffic. In

the implementation of the plan, partial solutions were made at the expense of

basic concepts and to protect private interests. In that way, there were destroyed

the last remains of the former church of St. Sebastian, such as was opened the

arch of a Roman porch on the antique Peristyle nearby existing church of St.

Rocco.[71]

- In 1923–1925 it was built behind

Prokurative square three-storey building called “Ševeljević” with a monumental

architectural vocabulary of the main facade. Later, it was "Mortgage

Bank".[72]

- In 1925–1926 it was built Meteorological

Observatory on the Marjan hill, designed by architect Josip Kodl.[73]

- In 1926 it was built the

customs and passengers office in the south port. Floor above the part of the

ground floor and a porch on the east side of the object were upgraded in 1929

by architects Fabijan Kaliterna and Alfred Keller. Riva was asphalted;

previously was paved only in a narrow strip along the coast, and in front of

houses near Diocletian's Palace as a narrow sidewalk.

- In

1927 it was built on Matejuška (fishing harbor in the waters of the city port)

"Gusarov Dom" with storage of boats, [74] by

Josip Kodl. Since its inception in 1921 and until 1927, the storage of boats of

this company was based in the big hut near the pier.[75]

- In 1928 it was opened a new cemetery east

of the city. At first it was called Pokoj, then Lovrinac.[76]

- In 1928–1929 it was pierced and decorated

the new main street of the former folk suburb Lučac.[77] In the same period it was built a "Fire Station" in city area

of Lovret.[78]

- In 1929 it was erected boundary wall around

the estate of Ivan Mestrović in the city area of Meje, with facilities for the

garage and apartment guards, according to the project of Fabijan Kaliterna.[79] A few years later it was built the villa (today

Meštrović Gallery), designed by the sculptor himself. On the main entrance is a

long porch with Ionic colonnade.

- In 1929–1930 it was built a great

five-storey building of insurance cooperatives "Croatia", designed by

architects Zlatibor Lukšić and Kuzma Gamulin.[80] Also, there were built two

buildings for primary schools “Manuš-Dobri” and “Veli Varoš”. The first one was

designed by Josip Kodl.[81]

- In 1930 it was built four-storey stone

building of "Commercial Craft Society" in the western part of the

city port, designed by Fabijan Kaliterna.[82]

- In 1931–1932 at the beginning of city area

of Meje it was built building of "Adriatic Guard" in which was

located the “Maritime Museum”.[83] In the same period it was arranged road from

"Split Pensions" at the Meje area to the western cape of the Marjan

hill, [84]

where was built a large stone building of “Oceanographic Institute” from 1932

to 1933,[85] designed by Fabijan Kaliterna.

- In 1932 it was completed the new

contemporary urban water supply system by the architect Feliks Šperc.[86] In the same year it was opened "Split Shipyard" in the Supaval

Bay on the north part of the city.[87]

- In 1932–1933 it was built the “Hygienic

Institute”, designed by the architect Ante Barač. In the same period it was

built five-storey “Pension Institute” in Hrvoje Street by the architect

Vladimir Subic from Ljubljana. It was the first residential building in Split,

which had an elevator.[88]

- In 1938–1940 at the end of the west coast

of the city port it was built five-storey “Ban's palace”.[89] Later, it being dropped idea of the construction of

the south lower building of “Ban’s Council”.

- In 1939–1940 it was built the “Ivanišević

Palace” (old newspapers building of "Slobodna Dalmacija") at the

start of King Zvonimir Street. This five-storey building, with curved facade

covered with stone, two bay windows and closing altana, was built according to

the design of Zlatibor Lukšić.[90]

- In 1940–1941 it was built a new, concrete

reinforced city beach "Bačvice", along the eastern side of the

Bačvice Bay.[91]

- In 1941 the Italians dismantled monument of

Gregory of the Nin by the sculptor Ivan Meštrović.[92]

[1]

''Contingent of the population in the cities/municipalities, the list of

2011'', CBS, accessed September 11, 2015, http://www.dzs.hr/Hrv/censuses/census2011/results/htm/H01_01_03/h01_01_03_zup17.html.

[2] J. Vrandečić, Dalmatinski

Kulturkampf ili ''sukob kultura'', [in:] Prva dalmatinska umjetnička izložba, ed. B. Majstorović, (Split 1908) edition Split 2010, p. 3.

[3] D. Kečkemet, Likovna umjetnost u Splitu

1900–1941, Split 2011, p. 11.

[4] Ibidem.

[5] S.

Piplović, Urbanistički razvitak Splita

između dva svjetska rata, [in:] Zbornik

1. kongresa hrvatskih povjesničara umjetnosti, ed. M. Pelc, Zagreb 2001, p.

145.

[6] In

1877 the first rail connection with the inland were established and in 1880 it

was extended. In the same year, the Diocletian aqueduct was revitalized, so the

city received water from running source nearby river of Jadro. Also, the coast

was secured and arranged at the east part of the port and protected by a

breakwater in 1887.

[7] S.

Piplović, Eklekticizam i secesija u

urbanističkom razvitku Splita, [in:] Peristil,

ed. V. Zlamalik, Zagreb 1988-89, p. 97-103.

[8]

Piplović, op. cit., p. 145.

[9] Ibidem.

[10] E. Šarić, Muzej

grada Splita, Split 2003, p. 125.

[11] Ibidem.

[12] Piplovic, op. cit., p. 145.

[13] Kečkemet, op. cit., p. 17.

[14] S.

Piplović, O geodetskim radovima u Splitu

početkom 20. stoljeća, „Geodetski list“ 1993,

no 2, p. 159-164.

[15] B. Radica, Novi Split: monografija

grada Splita od 1918-1930 godine, Split 1931, p. 3. All translations by

Author.

[16] B. Majstorović, Stalni postav

Galerije umjetnina, Split 2011, p. 23.

[17] T. Blagaić Januška, Arhitekti braća

Žagar iz fundusa Muzeja grada Splita, Split 2013-2014, p. 20.

[18] Ibidem.

[19] Ibidem, p. 9.

[20] Kečkemet, op. cit., p. 24.

[21] Blagaić Januška, op.

cit., p. 9.

[22] Kečkemet, op. cit., p. 14.

[23] M. Bošković, Prilozi za biografiju splitskoga

graditelja Marina Marasovića, [in:] Kulturna

baština, ed. S. Piplović, Split 2010, p. 205.

[24] G. Praga, F. Luxardo, History of

Dalmatia, Giardini 1993, p. 281.

[25] P. O'Brien, Mussolini in the First

World War: the Journalist, the Soldier, the Fascist, Oxford 2005, p. 17.

[26] T. Marasović, G. Marasović, A. Ganza, Vodič Splita, Split 1988, p.

33.

[27] Kečkemet, op. cit., p. 24.

[28] Ibidem.

[29] Nacija i nacionalizam u 19. i 20. stoljeću kao pojava i historiografski

problem na primjeru Dalmacije, Agencija za odgoj

i obrazovanje, accessed November 1, 2015,

http://www.azoo.hr/images/izdanja/manjine/07.html.

[30] Ibidem.

[31] Kečkemet, op. cit., p. 25.

[32] Blagaić Januška, op. cit., p. 29.

[33] Ibidem, p. 20.

[34] Ibidem, p. 29.

[35] Marasović, Marasović, Ganza, Vodič Splita…, p. 32.

[36] D. Kečkemet, Skica za sliku Splita između dva rata, „Mogućnosti“ 1992, no

8-9-10, p. 636-642.

[37] Ibidem.

[38] Blagaić Januška, op.

cit., p. 29.

[39] Z. Jelaska-Marijan, Grad

i ljudi: Split 1918–1941, Zagreb 2009, p. 63-142.

[40] Blagaić Januška, op. cit., p. 30.

[41] Ibidem, p. 29.

[42] Ibidem, p. 26.

[43] Piplović, op. cit.,

p. 146.

[44] Ibidem.

[45] Šarić, op. cit., p. 128.

[46] Ibidem.

[47] Ibidem.

[48] In

1979 the Diocletian's Palace was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

[49] Šarić, op. cit., p. 128.

[50] Piplović, op. cit., p. 145.

[51] D. Tušek, Arhitektonski natječaji u Splitu 1918-1941, Split 1994, p. 32-41.

[52] Piplović, op. cit., p. 145.

[53] Šarić, op. cit., p. 127.

[54]

Piplović, op. cit., 145.

[55] Ibidem.

[56] A. Grgić, Projekti

preinaka otvorenih javnih prostora povijesne jezgre grada Splita od sredine 19.

stoljeća do 1990-ih godina, [in:] Prostor,

ed. Z. Karač, Zagreb 2012, p. 163.

[57] Ibidem.

[58] Piplović, op. cit., 148.

[59] Šarić, op. cit.,

p. 129.

[60] Piplović, op. cit., p. 148.

[61] Povijesna splitska kupališta, narodni.NET

tradicija i običaji, accessed September 26, 2015, http://narodni.net/povijesna-splitska-kupalista/.

[62] Piplović, op. cit., p. 148.

[63] Šarić, op. cit., p. 128.

[64] Piplović, op. cit., p. 146.

[65] Blagaić Januška, op. cit., p. 56.

[66] Ibidem, p. 32.

[67] Ugasli sjaj stare slave, [in:] Otok Vis – edicija za kulturu putovanja,

ed. B. Karlić, Zagreb 2007, p. 203.

[68] Značajni urbanistički potezi te važniji objekti u Splitu 1806–1950', Split gradski kotar Gripe, accessed September 20, 2015, http://www.gripe.hr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=178<emid=127.

[69] Piplović, op. cit., p. 146.

[70] Šarić, op. cit., p. 126.

[71] Blagaić Januška, op. cit., p. 53.

[72] Značajni urbanistički potezi, op. cit.

[73] Piplović, op. cit., p. 148.

[74] Kečkemet, op. cit., p. 27.

[75] E. Šegvić, Matejuška,

[in:] Kulturna baština, ed. S. Piplović,

Split 2009, p. 143-188.

[76] Piplović, op. cit., p. 148.

[77] Ibidem, p. 147.

[78] Vatrogasci antifašisti, Slobodna Dalmacija, accessed

September 22, 2015, http://arhiv.slobodnadalmacija.hr/20031031/feljton01.asp.

[79] Šarić, op. cit., p. 128.

[80] Značajni urbanistički potezi , op. cit.

[81] Kodl, Josip, Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, accessed September 16, 2015, http://www.enciklopedija.hr/natuknica.aspx?id=32212.

[82] M. Bošković, R. Plejić, Dom

Trgovačko-obrtničke komore u Splitu; Doprinos arhitekta Fabijana Kaliterne u

promišljanju uređenja zapadnoga dijela gradske luke, [in:] Prostor: znanstveni časopis za arhitekturu i

urbanizam, ed. Z. Karač, Zagreb 2015, p. 56-59.

[83] S. Piplović, Počeci urbanizacije

splitskog predjela Meje, [in:] Kulturna

baština, ed. S. Piplović, Split 2010, p. 175-204.

[84] Značajni urbanistički potezi, op. cit.

[85] Piplović, op. cit., p. 148.

[86] Povijesni razvoj, Vodovod i kanalizacija Split, accessed September 15, 2015, http://www.vodovod-st.hr/Onama/Povijesnirazvoj/tabid/55/Default.aspx.

[87] Piplović, op. cit., p. 147.

[88] Značajni urbanistički potezi, op. cit.

[89] Piplović, op. cit., p. 147.

[90] Značajni urbanistički potezi, op. cit.

[91] Piplović, op. cit., p. 146.

[92] Dramatična štorija o splitskom spomeniku Grguru Ninskom, tportal.hr, accessed September 22, 2015, http://m.tportal.hr/vijesti/364801/Dramaticna-storija-o-splitskom-spomeniku-Grguru-Ninskom.html.

Thanks for sharing these ideas about using marble in interior design.

OdgovoriIzbrišibuilding development France

real estate development France

commercial building projects France

residential construction France

urban development France

property development companies France

mixed-use development France

sustainable building France

architectural development France

infrastructure projects France

Thanks for sharing these ideas about using marble in interior design.Irish property development

OdgovoriIzbriširesidential housing projects Ireland

commercial real estate development

EU construction standards Ireland

sustainable building initiatives

urban redevelopment Ireland

smart city projects

heritage site restoration Ireland

energy-efficient housing

local property developers Ireland

Thanks for sharing these ideas about using marble in interior design.Austrian property development

OdgovoriIzbriširesidential housing projects Austria

commercial real estate development

EU construction standards Austria

sustainable building initiatives

urban redevelopment Austria

smart city projects Austria

heritage site restoration Austria

energy-efficient housing Austria

local property developers Austria

Thanks for sharing. Our team provides affordable general contracting services across the UK

OdgovoriIzbrišibuilding development

building development agreement

building development approval

building development application

building development authority

building development companies

building development corporation

building construction examples in UK